Attachment Style & Spirituality

Note from Chuck: A Masonic brother and I were having a conversation in which this topic arose. After hearing what he had to say, I asked if he would write something up to be shared with others who might be interested in how some of their personality dynamics could affect their spirituality. He agreed to do so if he could remain anonymous. So, here you go!

It is cliche, but true to say that many of us receive lessons from caregivers in our upbringing, and that it sets the stage for our relationships. “It’s all about your parents”.

In our spiritual lives, relationships are still primary: whether student/teacher, friend/friend, priest/penitent, relationships and conflicts in them are constant. They are how we establish what is OK in the spiritual realm, and a primary part of how we get our information. This has led me to wonder about the connection between the two, and about how our psychology shapes the way that we engage with spiritual life.

In this piece I’d like to look at attachment styles discussed in psychology, and look for clues about how they might shape the spiritual paths people select.

A warning: in this piece, we will deal with broad trends and patterns of human behavior. When mis-applied, they become stereotypes which block understanding of an individual. They represent tendencies of behavior, not certainties. They can be useful as a part of a nuanced understanding of a person, but should not be substituted for that understanding. Put most bluntly: don’t use this to pigeon hole people.

Attachment Styles

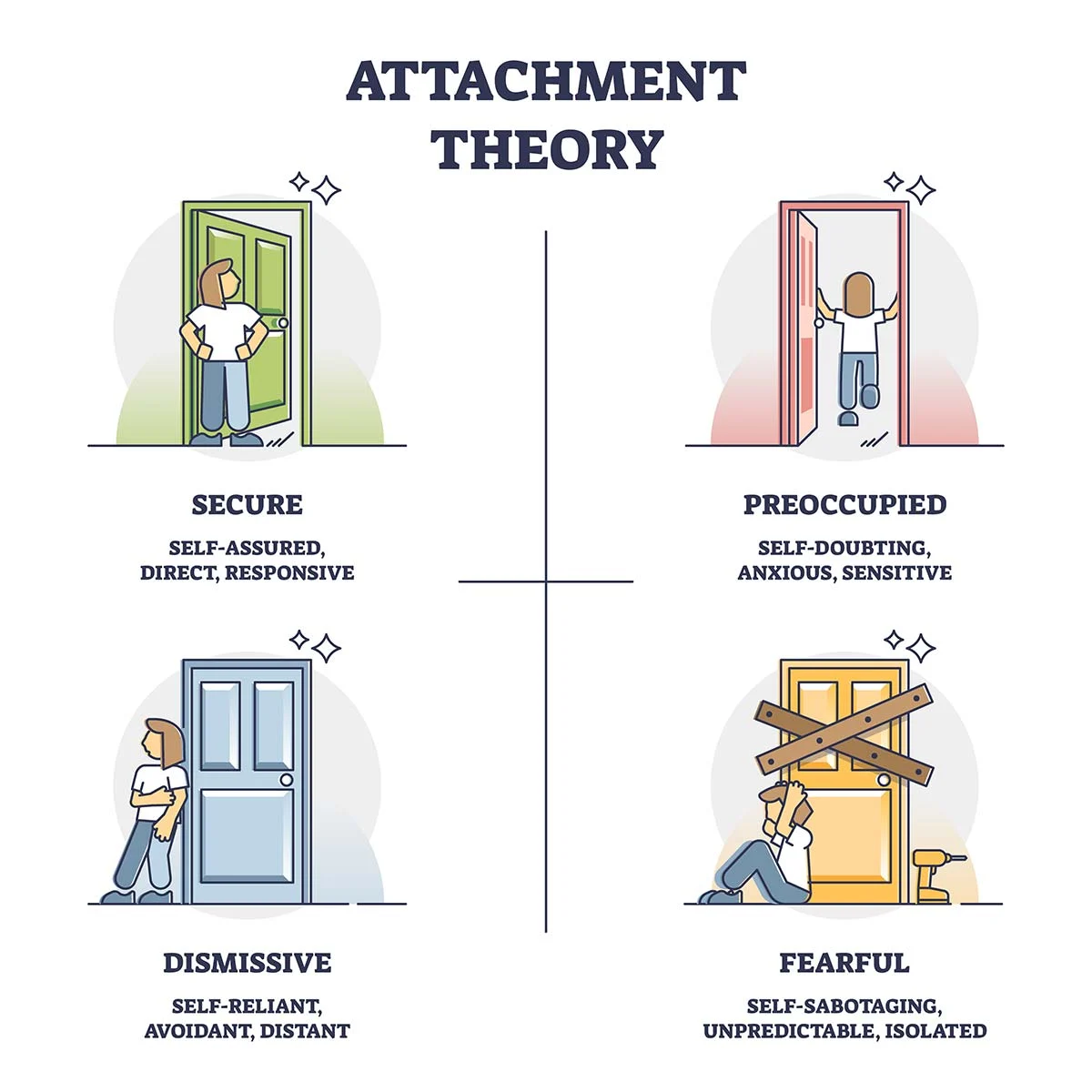

Attachment styles are patterns of behavior in relationships that people develop via early interactions with caregivers. As small children, most of us learn via mimicking behaviors in our homes, and responding to situations. The styles we develop as children become a sort of automatic heuristic, or patterned behavior we take into social and romantic relationships in life. The concept of these “styles” originated from the work of Mary Ainsworth and John Bowby, and are divided into four types.

It is important to acknowledge that these are broad descriptions, not specific recipes, where we may find resonant items but miss a perfect fit.

- Secure Attachment: people have a positive view of themselves and relationships. Comfortable with intimacy, they seek & offer support. They handle conflicts with some balance.

- Anxious Attachment (or Anxious-Ambivalent): people who often have low self-esteem, preoccupied with their relationships; they tend to be sensitive to others’ actions and attitudes, fearing rejection. They may be clingy, or need frequent reassurance.

- Avoidant Attachment (with two subtypes):

- Dismissive-Avoidant: people who create distance from others, they may feel that they do not need close relationships. They suppress their feelings, or distance to avoid conflict. Lone wolves, who may pride themselves on being self-sufficient.

- Fearful-Avoidant: people with a mixed view; desiring closeness but fearing to get too close. They may want intimacy but struggle to trust, due to fear of being hurt. This push and pull may cause contradictory behavior.

- Disorganized Attachment: thought to be caused by serious inconsistency in caregiving during childhood. A person may seem to have no clear approach in relationships, showing a mix: avoidance, resistance, clinging, euphoria, and so on. They expect volatility in people around them, and may appear confused or fearful.

Very rough estimates suggest 50 percent of the population is secure, 20 percent is anxious, 25 percent is avoidant and 5 percent is fearful. It should be noted that this is fluid, and some research shows a recent decrease in secure attachment and increase in insecure attachment in college students (Konrath, 2014).

The Spiritual Life: Where to Attach?

Seekers along the way meet authority figures, or even substitute parents. It might be the worshipful master of a Masonic lodge, a priest we call Father, an organizer, or even a cult leader. Those authority figures have organizations with their own dynamics ranging from warm, loving groups of individuals, to boring clubs, to toxic political power games, and every point in between.

The seeker approaches these groups to learn, grow, share community; he or she is looking to attach, and the group represents what there is to attach to. The seeker brings some kind of attachment style, and the group presents some set of patterned behaviors: they may be unpredictable, nurturing, balanced, abusive, or even an inconsistent mix.

Adapting (Granqvsit, 2013): “Spirituality capitalizes on the attachment system, and (…) believers’ perceived relationships with God can be characterized as symbolic attachment relationships”.

Collision of Style with Community

Imagine these scenarios like they concerned family friends of yours:

Suppose a person (“Alice”) with an avoidant style came into contact with a wonderful mainline church full of securely attached people who were warm, open, and balanced; a near ideal community! The sad irony is that Alice might hate it. The group might spend a lot of time well-meaningly trying to draw her in, involve her, and have her share in fellowship, while Alice distrustfully keeps them at arm’s length. The relationship may fall apart in months.

Suppose a person (“Bob”) with an anxious style came into contact with a dangerous cult. The leader expressed the need for absolute loyalty, criticizing and punishing members who defied his will. Bob would not enjoy this situation, because his value in the group would be permanently insecure. But it is possible to imagine this relationship persisting decades, as Bob chases approval. The cult might even raise a generation of children, similarly anxiously attached.

Suppose a person (“Charlie”) with an avoidant style begins to learn about mysticism and western esotericism. He might avoid communities entirely. His lone wolf attitude collides with material that speaks of solitary spiritual practice, and the two simply click. How long would this last? There is no telling. A dismissive avoidant who feels no need for relationships could carry it through a lifetime, and there is plenty of precedent for this among hermits and monastics. A fearful avoidant who still desires closeness might eventually be pulled into some form of community through a need to connect.

Which Union Did You Come For?

It’s humbling to consider how seldom we even know what we want. More mundane than lofty spirituality, if I ask people at work where they want to go with their careers the answer is usually, “I’m trying to figure that out”. Answers range widely and shift regularly. I frame possible answers as types of union corresponding to the Four Worlds of Kabbalah.

- Aziluth (Archetypal): Union with All

- Briah (Creation): Union with partner / community / others

- Yetzirah (Formation): Union with self / self-improvement

- Assiah (Action): Union with the way things are; improving my material circumstances

I believe our objectives may feel like a confusing jumble because in the four worlds, reasons in one world may coexist with different reasons in another world. It’s not one or the other, it’s both.

We now have three major moving parts in our spiritual lives: our attachment styles, the group we are (or aren’t) attached to, and our objectives for all of this, which may be unknown. This is what each of us navigates.

We navigate traditions in three ways I will describe:

- Those who pass through traditions (moving place to place, not attaching)

- Those who stay in one tradition (find something to stably attach to)

- Those who flee a tradition (attaching, later separating)

Those Who Pass Through

The origin of this article was my observation that in my circle, those who were interested in mysticism or the occult seemed to all be avoidant attachers, myself included. Why should that be?

In our culture, to arrive at forms of mysticism, you usually pass many options first: the dominant religion locally, study of comparative religion where you learn about “theological competitors”. You might learn about a dozen philosophies & sects, winnowing options, all while moving in and out of a confusing abstract fog called “spiritual but not religious”. It is also possible to avoid attachment to the questions themselves: it turns out that avoidants are more often agnostics. (Kirkpatrick and Shaver, 1992)

The mystically inclined move through many ideas and communities where they might have stayed; yet they persisted and went further. Avoidants have some fundamental element of maintaining individuality and distance. Perhaps they moved through traditions because they were less likely to attach. These people seem to me to have pushed past and through, seeking a kind of union – perhaps even unknown to them – but not as often a union with community.

Then there is, never to be discounted: pure experience. It is also known that people with disorganized attachment styles are more likely to have mystical experiences, and may be part of self-reparative processes (Granqvist, 2012), even though they can also be alienating experiences relative to mainstream communities.

Those Who Stay

Let’s look past avoidants. We likely all know regular parishioners of mainline Christian denominations. This is the sole source of their spiritual life, and they often feel entirely fulfilled by it. With my personality, frankly I could not understand them for quite some time, because I did not understand their goals and needs.

Both securely and anxiously attached people crave community and connection, even if for different reasons.There is science behind this, for example a study that established that secure and anxious attachment was a primary factor in spiritual development for a group of Orthodox Jewish women (Ringel, 2008).

Survey data is easy to locate, and people will tell you why they go to church. Note how many of these reasons are relational; dealing with children, community, or partner. Community is “not important” for only 10% of people. People’s goals appear to me to be layered, so note that closeness to God as a primary desire conflicts not at all with desire for community; people’s motivations are like sandwiches and there is always more space for more ingredients & layers.

For a mystic, it might be interesting to compare these motivations to one’s own, to note potentially profound differences in the way people frame their journeys.

Those Who Flee

Another mode we commonly see in spiritual life is a form of spiritual abuse and reaction to it. Many people raised in western traditions flee to eastern traditions such as Hinduism and Buddhism, explicitly rejecting their upbringing. Most famously when the Beatles went to India, but also including many famous counterculture figures like Ram Dass. Abuse of all sorts is very real. There are overt criminal acts like sexual assault, but more nuanced situations like dominating with dogma, and emotional neglect, which can create the misapprehension that the entire tradition is corrupt.

I would be willing to bet that each of us has either experienced some facet of this, or knows someone who has. Which is another way of saying “this is common”.

You may not be surprised to learn that the east has similar personalities who “flee to the west” in their spiritual lives, such as Mitsuo Aoki, raised Japanese Buddhist, who became a Christian theologian. It is notable for the purposes of this article that he was of Japanese descent, was raised during the horrors of World War II, as a Buddhist in a Japanese camp in Hawaii at the same time period of Japanese internment camps on the mainland. I never knew Mr. Aoki but I believe he had his reasons. Muhammed Ali is another example; raised Baptist, he later became Muslim, seeing no representations of African Americans among White Christianity, finding “everything Black being demonized”, perceiving Islam as a faith full of people who laughed with joy and helped one another.

Whether fleeing from West to East, or the other way, the important notion is flight: away from your home tradition, and abusive circumstances, with hope of finding a place where attachment and union is possible. I frame this as “flight” and not as “emigration” because in my experience people are more motivated by escape than by the compelling aspects of wherever they are going. Anxious attachers might recognize this, fleeing abuse felt from chasing confirmation that would never come – and avoidants may recognize this as fleeing under the assumption they could never fit in, connection wasn’t possible.

With this full context, I get to this impactful quote I found in a book written by Chuck Dunning:

“thus, I chose to make a watchful, collaborative peace with my Christian identity rather than spend the rest of my life either in denial of it or at war with it” (Dunning, 2023)

This “opposite of flight” hints at the possibility of a reconciliation. It hints at the potential for peace in the interior sense, whether we are Christian or not.

It Explains a Lot

Given estimates above, that roughly 50 percent of the population is secure, 20 percent is anxious; if such people readily attach to communities at a higher rate, you would expect to see much larger churches than esoteric orders. There would be a lot of people who “stay”.

I might expect to see relatively small esoteric and mystical orders. “Those who pass through” are few in number, because it’s quite a long and hard road to have been filtered to that point. In such groups, we might expect frequent schisms and disagreements. What would happen if you got a group of predominantly avoidant people together? They’d do en masse what they’re accustomed to: assert their individuality, and struggle to attach to groups.

I would also expect a lot of people to flee. In 2024, information transparency on the internet makes it very easy to discover and widely publicize abuse of all forms. This combines with the same availability of information promoting alternative spiritual paths. Irrespective of an individual’s attachment style, they can flee. This is an aspect of modernity; flight from one’s home tradition was near unthinkable in 17th century England, today it is common; the difference is information and normalization. Flight would be common, so long as spiritual abuse & neglect is common and knowledge of options is available.

Conclusion

It is striking how other people’s and our own behavior in relationships, even when it is seemingly erratic or even random, makes a deep kind of sense when we attempt with empathy to consider the full circumstances and riddle of that person’s life.

In individual application, this information has caused me to speculate about ways I have reacted in the past towards spiritual communities, and about the personal subtext of my current relationships in those. I find insights often arise from a kind of gentle curiosity applied to those situations: what exactly was that group offering me? What did they expect of me? What was I looking for at that point in my life? Explorations of those topics often yield insights into the “why” behind what happened. When I see conflicts between other people, the same frame of mind helps me to adopt a balanced view of empathy for both in the presence of recognizing the hard facts of the situation.

I hope these thoughts might outline one piece of the puzzle, with some potential to shed light on previous decisions, or motivations for current ones.

(Cutting room floor extra stuff & notes)

Who among us hasn’t been a fish out of water at one point? Our differences and their impacts on relationships are profound:

- Tolerance for rules (group union) vs. design of one’s own system (autonomy). (if you want a humorous image, imagine how Aleister Crowley’s personality might have done trying to be a good Catholic)

- Desire to please others, vs. desire to seek separation (for a laugh, imagine an extremely introverted monk leading a worship service or consoling a large family)

Fish gotta swim, birds gotta fly.

——

Mystical and occult knowledge is hard to obtain. The texts are on the Internet, but making sense of them requires a lot of self-preparation. Many know the feeling of reading a text again and experiencing “ahhh I finally get it”. The words were clear the first time, but you were different. In this way, the knowledge is hard to come by. It isn’t widely understood, and so it isn’t taught, and so it must be sought. How implausible it would be to ever find yourself in an American high school class learning about the Kabbalah!

—–

I have no judgments. There are layered reasons why things are as they are. We grow as children as best we know how, yielding profound consequences looked at in full scope. It is no wonder it seems there are as many paths as individuals. Instead of judgment, consider gentle curiosity. “Hm. I wonder why that is that way?”

I have no advice. I know my experience: frequently difficult and discouraging. I know my plan: orient towards the heart, and love itself. Accept the facts of the past, leave the door to future independence cracked open. Our choices are not pre-ordained, but our styles and proclivities are constraints. They can be bent, they are not laws of physics that govern us. When bewildered, use love like a compass to find the path. Again with the gentle curiosity: “Hm. Which way leads to more love?”

So many paths, it’s bewildering.

Many wander, my hope is that we find a home. Many struggle to connect, my hope is that we find a way to do so. Many seek some kind or another of union, I hope you attain it. If you’ve already arrived, bring us along if you can. This is what I hope for you, whether you stay in your tradition, pass through, or flee it.

Lit Review / text from Chuck

Several studies have explored associations between adult attachment style and religiosity. They have found that individuals with a secure attachment style tend to have higher levels of religiosity, more positive images of God, and greater feelings of closeness to God than those with insecure styles (Byrd & Boe, 2001; Eurelings-Bontekoe, Hekman-Van Steeg, & Verschuur, 2005; Grandqvist & Hagekull, 2000; Kirkpatrick, 1998; Kirkpatrick & Shaver, 1992). Individuals with more positive images of self (secure and dismissive attachment styles) tended to have more positive images of God, while those with more negative images of self (preoccupied and fearful) tended to have more negative images of God. This was particularly true if respondents also reported that they were under particular psychological stress (Eurelings-Bontekoe et al., 2005). Preoccupied and fearful adults also reported having more experiential and highly emotional religious experiences, such as speaking in tongues, becoming born-again, or finding a new relationship with God than the other styles (Kirkpatrick, 1998; Kirkpatrick & Shaver, 1992). Participants identifying themselves as having avoidant romantic relationships tended to report being agnostic (Kirkpatrick & Shaver, 1992). The studies mentioned above have focused on religiosity rather than spirituality and thus have not explored the purpose and meaning aspect of spirituality. In addition, they have not explored the relationship between spirituality and attachment style.